Disturbing Romance: The Participatory Art of Dating Simulators

How can dating simulators confront people with uncomfortable realities? ‘Dating sims’ allow players to engage with virtual partners through scripted interactions, often reflecting and reinforcing real-world dynamics of courtship. However, beyond their entertainment value, some dating simulators function as a form of participatory art, using interactivity to critique contemporary romantic and social norms. This article demonstrates how ‘dating sims’ can serve as both a creative medium and a critical commentary on digital-age relationships.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The rise of digitalisation has reshaped human relationships, shifting many social interactions into virtual spaces. This transformation is especially evident in the realm of romance, where dating no longer requires face-to-face communication. From gimmicky dating apps to virtual AI girlfriends, technology has redefined intimacy, blurring the line between human connection and digital simulation.

Dating simulators, or dating sims, are a long-standing game genre, a precursor to many modern developments in digital romance (Pollack, 1996). They allow players to engage with virtual partners through scripted interactions, often reflecting and reinforcing real-world dynamics of courtship. However, beyond their entertainment value, some dating simulators function as a form of participatory art, using interactivity to critique contemporary romantic and social norms. This article explores two such examples: Doki Doki Literature Club! and The Game: The Game, to analyse how this genre can serve as both a creative medium and a critical commentary on digital-age relationships.

Back to topThe In-Between of Participatory Art and Games

Participatory art, as a term, has an ambiguous definition. However, it can be broadly described as art that involves the active participation of the audience, blurring the distinction between the artist and the public, existing as a work of collaboration (Bishop, 2006). The link between video games and participatory art has been described by Raessens (2005), as he establishes how the interactive nature of games actively involves the players in the process of creating their own unique experience akin to how ‘traditional’ art in this genre involves active participation of the audience as a part of the piece.

Dating simulators are a type of game in which the player’s objective is to interact with one or more love interests through multiple-choice dialogue or narrative. The choices then affect how the player experiences the game - how they build relationships with a character, what situations they get into and how their story will end. Raessens (2005) proposes to categorise different degrees of how players interact with games, three of which are crucial to the understanding of how dating sims relate to participatory art: interpretation, i.e. the way the player understands the content; deconstruction, i.e. the way the player interacts with the software of the game; and reconfiguration, i.e. the way the player interacts and reconstructs the narrative or the world of the game. Interaction through interpretation involves active participation as each player discovers and places their meaning into the game.

In the case of dating simulators, the person playing derives their perspective as they make their choices, shaping their experience of pursuing the ‘love interests’ and exploring the game's main narrative as they initially approach it. Deconstruction implies that the player looks into the game's programming to gain a new perspective on how it works to achieve different outcomes, interacting with the code and looking into the files. Reconfiguration, however, addresses how the players apply different tactics and pursue different narratives within the game to achieve a certain outcome, participating by trying various available actions to reach different endings.

Therefore, through their interactive narratives and player agency, dating simulators align with the core principles of participatory art. Players are involved in the narrative as they partake in interpretation, deconstruction, and reconfiguration. These games blur the lines between the artist (game developer) and the audience (player) and foster a collaborative experience within the game's defined framework. As a result, the commentary of the piece is delivered through the playing experience.

The games utilise the theme of romance and courting for commentary rather than plain entertainment.

The games this article will discuss are more intricate in their storytelling methods than regular dating simulators. The structure of interactive and choice-driven storytelling remains. However, the games utilise the themes of romance and courting for commentary rather than plain entertainment. These games have characteristics of Finklepearl’s (2014) classification of antagonistic participatory art. This category includes works of art which explore and challenge social norms through confrontation and destabilisation. However, while Finkelpearl often describes a lack of consent from participants in traditional antagonistic participatory art, these games only allude to that notion. Participation and decision-making in games are optional, yet these developers manipulate the gameplay to simulate a feeling of absence of consent from the participants or their in-game personas. Playing and making choices is voluntary, but the games shift their narrative to produce a sense of lack of participants’ or their characters’ consent.

Back to topLove, Literature and Horror in Doki Doki Literature Club!

Doki Doki Literature Club! is, at first glance, a simple anime-styled dating simulator, but as the player follows the narrative and pursues one of the love interests, the game shows elements of psychological horror. The player is invited to choose a name for the main character; a male teenager who joins his school’s unpopular Literature Club at his childhood friend’s (and potential love interest) suggestion. From there on, the player gets to create poetry to impress three of the four club members and engage in the new routine of the main character as everyone prepares for the school fair (Van Den Oudenalder, 2020).

The game is reminiscent of the original Japanese dating simulators, both the setting - a high school and an extracurricular - and the love interests - a childhood best friend, a shy girl, a mean but cute girl and an (at first non-romanceable) popular girl - are very stereotypical and common in this genre of games (Wright, 2017). However, as the story unfolds, heavy topics become prevalent, as the narrative explores mental health while providing a metanarrative about the genre of dating simulators themselves. While the player actively pursues one of the three available love interests, they start discovering the troubles these girls are going through. The atmosphere of lightheartedness quickly turns to disturbance as the themes of low self-esteem, self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and domestic abuse are raised by the love interests who open up to the main character. The player gets to participate in uncovering the game's plot as they interact with different routes and choices, ultimately constructing the story through their interpretation.

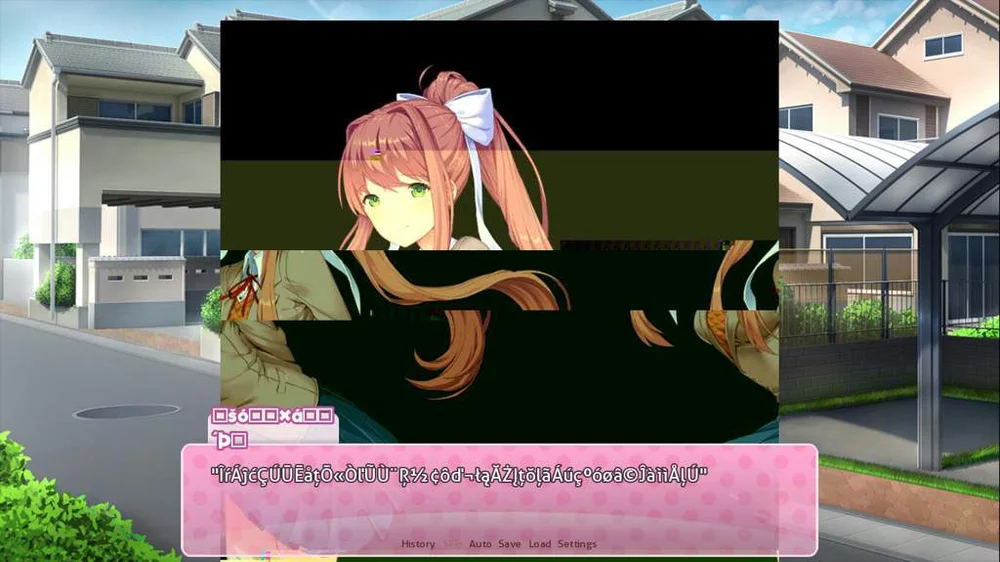

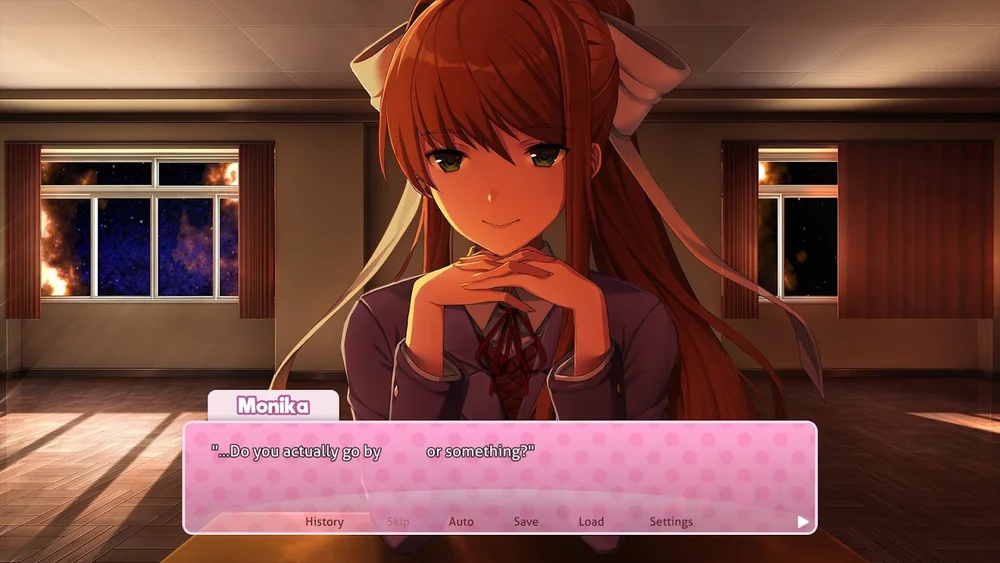

Further into the playthrough, the player is invited by the narrator to interact with the game files, open folders, view disturbing imagery and read the text documents suddenly appearing amongst codes and other software of the game. This element of the game’s deconstruction is another way of participation the player has while engaging with Doki Doki’s content. The game constantly restarts, and the player gets to play the story again. However, this time, the game is interrupted by mysterious errors. The plot later reveals that the game is corrupted, and the code gets constantly rewritten by Monika, Literature Club’s president. Monika is sabotaging all the other love interests due to her infatuation with the player. The chosen name of the main character gets replaced by the name that the player has entered in their computer’s account, and the game resumes with a constant state of dialogue with Monika.

Doki Doki Literature Club! utilises shock value to develop its narrative and address the genre of dating simulators and how they dismiss the humanity of female characters to pursue the male gaze. The player watches the game sexualize the love interests while opening up to the main character about their daily struggles. The mini-game, in which the player writes poetry that one of the girls will relate to with the sheer intention of romancing them, further establishes a flawed dynamic. The game invites the player to participate in objectification of the love interests, which is a common element in dating simulators that cater to the male audience (LaFrenier, 2022). However, the game proceeds to reverse this role so that the player experiences being objectified, as they get obsessively interrogated and ‘wooed’ by Monika while their previous progress gets erased and all other romanceable characters are killed off.

Thus, Doki Doki Literature Club! employs the participation of the players by engaging them in the process of the game, making them develop a perspective and see the real side of each love interest through multiple-choice dialogue and mini-game, viewing and decoding disturbing content within the game files. These interactions align with Raessens’ (2005) notions of deconstruction and reconfiguration, as the player is forced to move beyond passive consumption and directly manipulate the game’s structure to uncover its underlying critique. The traditional power dynamic of dating simulators is reversed; it turns the player into the object of desire, disrupting their sense of control. In doing so, the game embodies Finkelpearl’s (2014) concept of antagonistic participatory art, creating an experience where the player, despite their supposed agency, is gradually stripped of autonomy. This deliberate destabilization of participation forces players to confront the problematic tropes of the dating sim genre, illustrating how interactivity can be weaponized to expose the mechanisms of objectification within digital romance. This radical critique paves the way for a successor, The Game: The Game, which builds on DDLC's foundation to further push the boundaries of participatory art as a tool for social commentary.

Back to topPOV in The Game: The Game: Going Out as a Woman

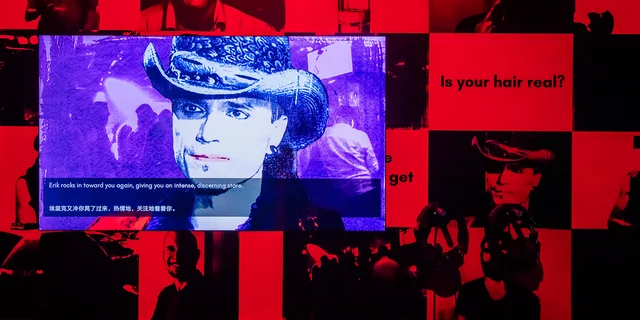

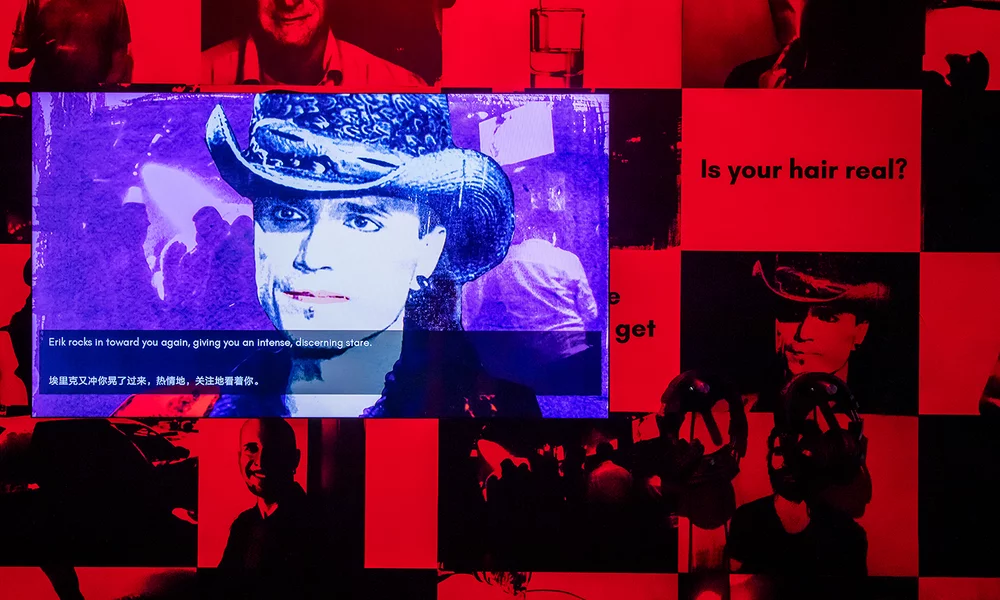

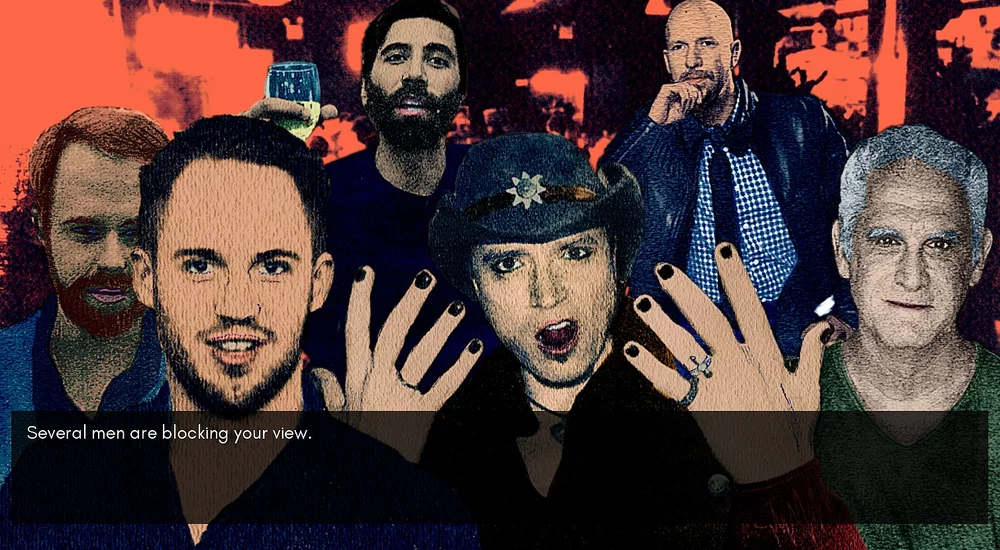

A project called The Game: The Game, developed by an artist Angela Washko, is a dating simulator game based on the author’s research into online pick-up artists, which is available online but was also debuted as an exhibition in New York’s Museum of Moving Image and later in other museums as well (The Game: The Game, n.d.). The game's setting is a first-person experience of being a woman during a night out in the club, as the main character gets approached by one ‘pick-up master’ after another. The atmosphere of the game is meant to be unsettling; the music by the band Xiu Xiu sounds like it came straight from a slasher, and the art style looks eerie, all to accompany the distressing nature of ways the different men in the club approach the main character. The player is in charge of how the main character responds to the aggressive flirting they are met with from the men, choosing to either outwardly refuse their advances or play along to see through their strategy and witness the intentions behind their ways of behaviour.

While The Game: The Game was presented in a traditionally participatory way, as an exhibition in which the audiences could play in a dimly lit space with multiple computers running the game and walls decorated with the game art and quotes of pick-up artists, the mechanics of the game itself are participatory. When describing Washko's project, Museum of Moving Image curator Jason Eppink mentioned that: “...it also makes you complicit in their frequently dehumanizing behaviour: refusing their advances results in a brief game. Only by actively consenting to participate in your suitor’s methods—which can range from cheesy to violent—will you be able to more fully understand them” (Net Art Anthology, 2016). The dimensions of required player participation then span from, firstly, them experiencing a route they decide to test in the first playthrough and how the game will affect them and, secondly, them applying strategy to achieve the variety of endings to fully experience the methods of “seduction”.

Washko’s project results from intensive research into the community of pick-up artists. The practices and phrases featured in the game were derived from interviews she conducted with the “gurus” themselves, as well as the materials they provide for their students online. This has created an immersive experience within the game: the player gets to witness the courting of pick-up artists from the viewpoint of a woman trying to find her friends during a night out (Hudson, 2020). The choices the player makes do not lead to a happy ending for the main character and safely returning to her group of friends; instead, fleeing from one uncomfortable encounter starts another, potentially an even more aggressive one.

While unsettling, the game works to portray the reality of such men’s approach to romance, driving home the idea of how dehumanizing their actions are toward women by making the game a first-person experience of such advancements. By immersing players in its world, The Game: The Game exemplifies Raessens’ (2005) concept of interpretation, as players must actively navigate and process the unsettling interactions they encounter. Furthermore, the game demands reconfiguration, as understanding the mechanics of pick-up artist strategies requires repeated engagement with different routes, exposing the underlying structures of power and control. Washko’s work also connects to Finkelpearl’s (2014) idea of antagonistic participatory art, as digital gurus force themselves onto the player with no option to escape, no happy ending or perfect playthrough. By making player involvement essential to experiencing the game’s message, The Game: The Game turns interactivity into a form of criticism, using the dating simulator format to reveal and challenge the way women are treated both in games and in real life.

Back to topGame Over

Analysing the contents of Doki Doki Literature Club! and The Game: The Game has revealed how the format of the dating simulator genre can act as a platform for participatory art and social commentary. The findings showed how both games employ Raessens' categories of participation in games, namely how they make the players interact with choice-making to construct a cohesive narrative and derive meaning, deconstruct the storyline as they explore the possible routes and experience what the game has to offer through its choices and reconfiguring the physical files of the game to gain more insight into what messages are left out of the player’s sight while they are engaging with just the gameplay.

The games provided an experience which uses immersion and provocation to get the players thinking and put emphasis on social issues.

The examples used to portray the diversity of participation in the dating simulator genre have shown the important ideas that went into constructing said experiences. The artists and development teams create games with their participatory nature in mind to emphasize social issues, spanning from the flawed nature of the dating simulator genre originating as a platform for female objectification to exploring other impacts digitalisation has had on romance, illustrated with the example of the online community of pick-up gurus. The games provided an experience that uses immersion and provocation to get the players thinking, employing a popular format and creating a well-thought-through experience.

Back to top

References

Bishop, C. (2006). Introduction. In Participation: Documents of Contemporary Art. The MIT Press.

Hudson, L. (2020, April 16). Dating sim meets survival horror: the game that exposes pick-up artists. The Guardian.

LaFrenier, T. (2022). Horniness and heartbreak: DDLC and the male gaze. The Michigan Daily.

Pollack, A. (1996, November 25). Japan’s newest young heartthrobs are sexy, talented and virtual. The New York Times.

Raessens, J., De Mul, J., & Rushkoff, D. (2005). Computer Games as Participatory Media Culture. DiGRA Conference, 373–388.

The Game: The Game. (n.d.). angelawashko.com.

The Game: The Game. (2016). NET ART ANTHOLOGY.

Oudenalder, A. van den (2020). Are you cheating?: The relationship between agency and breaking the fourth wall in Doki Doki Literature Club! [Bachelor’s dissertation, Utrecht University].

Wright, S. T. (2017). Doki Doki Literature Club! hides a gruesome horror game under its cute surface. Pcgamer.

Back to top